Wallace Wyss is both a working photojournalist and a fine artist. Here he explains how he uses light to create “art” with photographs, which are then used as inspirations for his oil paintings.

I wear two different hats. I attend car shows, from “cars’n’-coffee” informal events to the world’s poshest concours d’Elegance. My role is normally that of a photojournalist, taking pictures to go with my event reports for Internet sites, magazines or for my Incredible Barn Finds series of books about rare cars that are sometimes found in derelict condition.

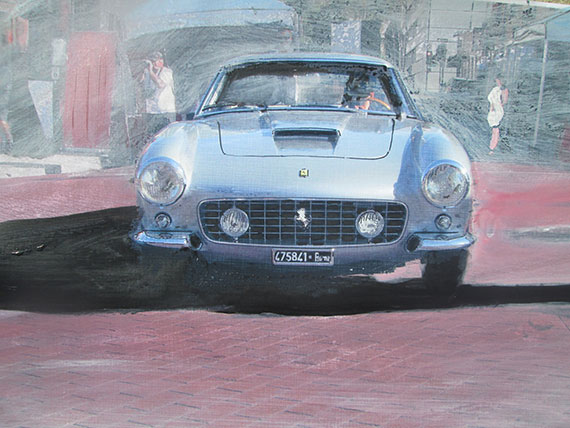

Sadly there was not enough people behind it in real life to convey the on-the-street concours atmosphere. I added a woman on the right but overall it is still too subtle a painting to be one of my favorites. Should have done the race car instead, at least that would be interesting as a factory racer.

But before I even put on that photojournalist hat, I arrive at each show with a second “hat”—that of a fine artist attempting to capture a car in a certain light and with a certain background with the goal of eventually making a painting. Alas that kind of picture requires a different mindset than “shooting for the record.” As an artist, I am “shooting for art.”

Ferrari swb 250GT front-on view. Although this street Ferrari wasn’t as dramatic as a racing version of the same model parked only a few feet away, I thought the silver on rose colored bricks pleasing.

And I’m here to tell ya that those two roles don’t necessarily mesh; often they fight each other tooth and nail.

For example, when I went to the Ferrari Club of America Southwest Region concours on Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena in April, my overall assignment was to select the most interesting cars and shoot them for a straight news story (“Here’s what was there, yadda-yadda”).

That’s because the editor at the websites that receive my photo reports don’t want to hear about art; all they want is “fully lit” pictures that show the whole car. So starting about 9am I dutifully change over, put on my photojournalist hat, and start shooting 30–40 pictures as a photojournalist.

A Quick Word About Equipment

In my film days, I carried a Nikon F3 with a zoom lens, wide angle, etc. But I gave all that up in favor of two digital identical Canon A2300 Power Shots, which will run you about $ 60 each at a pawn shop. They will shoot up to 1,000 pictures with a 16 MB memory card but you might have to carry a spare battery if you plan to shoot that many in one day. The advantage is small size—I wear them side by side in cases on my hip—but the disadvantage is a fairly ineffectual telephoto and also a firm resistance to shooting fast. If a car is moving, I can’t get two shots off quickly as I could in the old Nikon.

One thing that’s an advantage and disadvantage at the same time is the slight wide angleness of the lens. It turns out to be perfect for the sports cars I shoot. If I stand 3 to 4 feet away, the front of the car is bulges out and makes the car look “macho.” But if I am just a couple feet farther back, it is too far and the car loses its “macho” effect, looking much more pedestrian. My graphics consultant and photographer in his own right, Rick Bartholomew, who shoots 500 pictures per show, says I should also shoot from knee height sometime for more drama, and I occasionally remember to do this. Rick also shoots with a selfie stick to get that unusual from-on-high angle.

Painting with Light

Now back to the car shows. When I first arrive, I wear my artist’s hat so I can ”paint with light,” a phrase I got from Ansel Adams. (I knew the famed photographer because he was often an honorary judge at the famed Pebble Beach concours). I interpret his catchphrase to mean, as the sun comes up, the light is rapidly changing as you watch, and, if you have pre-picked the subjects and are ready to shoot, you can “paint” the contours of whatever you are shooting as the light gets stronger.

White Daytona. White is the most difficult color to shoot, black send most difficult. I got here just in time to get the sun painting the subtle hood contours but am still deciding whether to make a painting; other cars with better colors are taking priority in paintings.

In mid-winter I have seen the morning light go from dark to fully lit in a matter of five minutes so it’s prudent to pre-select just two or three cars you want to shoot “artfully” because you won’t have a chance to capture more before they are fully illuminated.

The only trouble is, the light isn’t as strong in spring as it often is on a bright clear winter morning. If I get there early enough, I usually succeed, capturing the forms of two or three cars that would have been impossible to see any subtleties in once the sun was fully up; the most difficult of all being an icebox white car like the Ferrari 365GTB/4 Daytona I shot in Pasadena.

So if you want to try out for yourself Adam’s “paint with light” philosophy, I heartily recommend arriving at your next car event at dawn—or even about 10 minutes before sunrise.

A Second Chance, Near Sunset

Now some who fail to set their alarm clocks arrive late and say, “Well, there’s always sunset.” True, there may be a second opportunity, in that there is often a nice “golden light” at the end of the day if there are not many clouds. But I can’t tell you how many times in the past when I raced to catch that last bit of sun (when I can move the car to the location) only to find a fog bank is out there unseen but enough to kill the chance for the golden light. Plus the logistics are that most concours are over by 3pm so, just when the light could be at its theoretical best, the cars are gone.

An Experiment in Back-Lighting

Back in the 20th Century, when I used to shoot with film, I would never shoot into the sun, because with a set film speed, and seeing film has such a limited range, that doesn’t include coping with the intense light of the sun. But now shooting digitally, I have a fresh opportunity with an ever changing capability in my camera to try shots with the sun behind the car, my goal in this being to wash out the background but still keep some color in the car. My goal here is to keep some background for ambiance (to show the setting) but use the strong backlight to “wash out” the details, to reduce them to insignificance, so they won’t compete with the subject car.

Creating Ambiance with the Setting

A goal of many of my “shots for art” is to not only show the car but show the setting I saw the car in, that is if you feel the setting “tells a story” about the car. Now when I went to the Pasadena Ferrari show, I hope there would be heavy ambiance due to the fact that the buildings in Old Town on Colorado Boulevard are old enough to be ornate in the style of the 19th century. Especially appreciated are the ornate filigrees on some buildings and the palm trees.

The drawback was the usual placement of the cars—the majority parked cheek-by-jowl next to each other at a 45 degree angle with only a few selected ones chosen by the organizers to be displayed out in the center of the street, but those were too far away from the buildings to get nice architectural details immediately behind them.

Of course once I pick up a paintbrush, as a painter, I have the choice of putting the car against any background I want, but the ideal if you’re capturing ambiance is to have the car against the same background you caught on film. That’s because the shadows will be different on the car and the background if you use a car from one picture and a background from another, the shadows won’t match, especially if the pictures are shot hours apart.

Isolating One Background Element

At another event, staged at a magnificent mansion in Beverly Hills once again the organizers had the cars parked side by side in a parking lot. So I couldn’t get the red Ferrari Daytona Spyder moved to where the Gatsby style mansion would be visible in the background (concours entrants do not move once they’re parked) so I thought, well, I will shoot tight so that eliminates any distractions like the car next to it. I was happy with the way the red paint came off (even though the picture was shot way past sun-up at about 9:30am) I did a painting of the car anyway but left in only one part of the in the style of Ken Dallison, hoping just a bit of the stone fence would put the car in context as it were. I don’t like the fence I painted but it is still preferable to having the car floating against a white background with no suggestion of the setting.

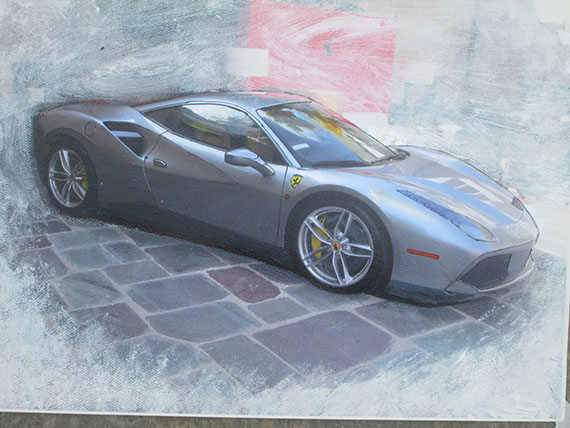

At the same show I had a chance to shoot a dark grey Ferrari 488GTB. New model, so I know there will be fans who want a painting of it when I have my art booth at Concorso Italiano in Monterey. But the bad news was that it was parked in shadow. I could wait until noon to get strong sunlight from above but then it would be too contrasty coming straight down. Still, I didn’t want to neglect the chance to portray a European car on the cobblestones of the mansion so I shot it and made a painting, but the whole thing comes across as a bit too monochromatic, many shades of gray—wish I could have had the whole car defined by rising sunlight with the gray all behind it but in that narrow courtyard that wasn’t going to happen–when the sun did get directly overhead it was going to be strong.

Choosing a Candidate for “Art”

Once I come home from a car show, and have dutifully filed the “news” pictures for a news report to whatever website wants it, I can finally kick back relax, pour myself a cuppa Java, put on some jazz, and don my artist’s hat to review the results of the day’s shoot all over again to see if any have any artistic possibilities. As usual, 90 percent I deem throwaways as far as “art,” because to me, they were totally pedestrian, and had no dynamism whatsoever. They weren’t what I call “art.”

Bad Photo: California Spyder. Great car but I was, at 5 feet , alas, too far away, making car look boring.

Why not just forget the background and just portray each car against an all-white background so the car is 100 percent the subject? If you go that route, you are throwing away any opportunity to capture the ambiance of the event a car was presented at and that would be a crying shame because many “concours” type car shows are in magnificent settings (such as the Pebble Beach concours which takes place at one of the poshest golf course in America, one right on Carmel Bay).

Good Photo: As I stepped two feet closer, the wide angle came up with more pleasing angles. This car is very curvy but you have to be close to capture that.

If I capture the car in its show setting, the viewers of the painting can get a sense what it was like to be there. (My favorite of my own paintings is my portrait of a Talbot Lago at Pebble, where you see the crowd thick around the car).

Diffused Effect

I don’t know if that’s what photographers call it but at another venue, an all-Porsche event called Rennfest, I found a Porsche 356SL (a lightweight racing Porsche) parked up on a stage. Now by the time I found this car, it was bright sunlight, and like I said, I don’t do bright sunlight for “art.” But in this case the car was brushed aluminum so that dulled finish automatically diffused any glare. Plus Porsche had artfully placed a more modern racing Porsche (a 917) nearby so here was the opportunity to show an example of Porsche’s earliest racing history along with a car symbolizing their later racing history, if only I could manage to downplay the car in the background.

I knew the red car, if painted in bright red, would distract from the main subject so, after painting the whole scene in natural colors as in the photo, I applied what is becoming my signature, a “veil of fog” over the whole scene except for the old aluminum Porsche so it would stand out as the main subject.

As I write this, I am planning a five day expedition to Monterey for the annual Car Week. I will probably shoot about 500 images in all but only 5 to 10 will end up being the subject of one of my oil paintings. Hopefully, when I man my booth at Concours Italiano an enthusiast who likes my work but wants “his car” will commission a painting, and that’s always fun. Often, if they have their car there, I go right out and shoot it so I have something to work with.

Grey car in gray shadows on gray cobblestones. I would have passed it up, but having the chance to shoot a European car on a European-like setting was too good to pass up, so I made a painting.

On that same trip, I will be wearing the photojournalist’s hat, “shooting for the record” to add more pictures to my Porsche 356 Photo Album book. If you ask, “Which is more fun—to shoot as a photojournalist or to shoot as an artist?” I have to say “artist” is preferable, but it’s a bit nerve wracking in that you don’t really know if you have it “on film” (as you used to say in film days) until you get home and examine each frame individually. As a legacy of having learned with film, I still don’t take enough pictures when—given enough memory cards and spare batteries—I could take thousands. I’m still in school in that regard.

About the Author:

Wallace Wyss provides a list of his available prints to anyone who writes him at photojournalistpro (at) gmail (d0t) com.

Go to full article: Painting with Light: A Photographer Shoots for Art

What are your thoughts on this article? Join the discussion on Facebook

Article from: PictureCorrect

The post Painting with Light: A Photographer Shoots for Art appeared first on PictureCorrect.