Many cameras have viewfinders, even though they have a screen on the back for viewing and composing pictures. In fact viewfinders are considered a must-have amongst enthusiasts and professionals, partly because they’re much easier to use in bright light where regular screens can be hard to see, and partly because for many people it’s more natural to put the camera to your eye than it is to hold it at arm’s length.

Some lower-end cameras don’t have viewfinders, relying solely on the screen on the back of the camera for composing photos. That won’t suit everyone, but for those who’ve only ever used a smartphone beforehand, it’s probably fine.

Direct vision viewfinders

These are the oldest and simplest type, but not used much these days. Most viewfinders today show you the view through the camera lens, but direct vision viewfinders are separate. They point the same way as the camera and have roughly the same angle of view, but they’re simply approximate framing devices rather than accurate renditions of what the camera lens sees.

Old snapshot cameras used direct vision viewfinders because they were cheap and simple, and they’re still used for instant cameras today. At the other end of the market they’re used for their clarity and immediacy by Leica in its rangefinder cameras and by Fujifilm for the hybrid direct vision/digital viewfinder in its X100F and X-Pro2 cameras.

They might not be as accurate, especially for close-up shots where parallax shifts can cause framing errors, but direct vision viewfinders do have some advantages. One is that they are very bright and clear. Another is that a ‘brightline’ frame shows you clearly what the camera will capture but you can also see a little outside the frame too, which can be helpful for anticipating the action.

Optical viewfinders

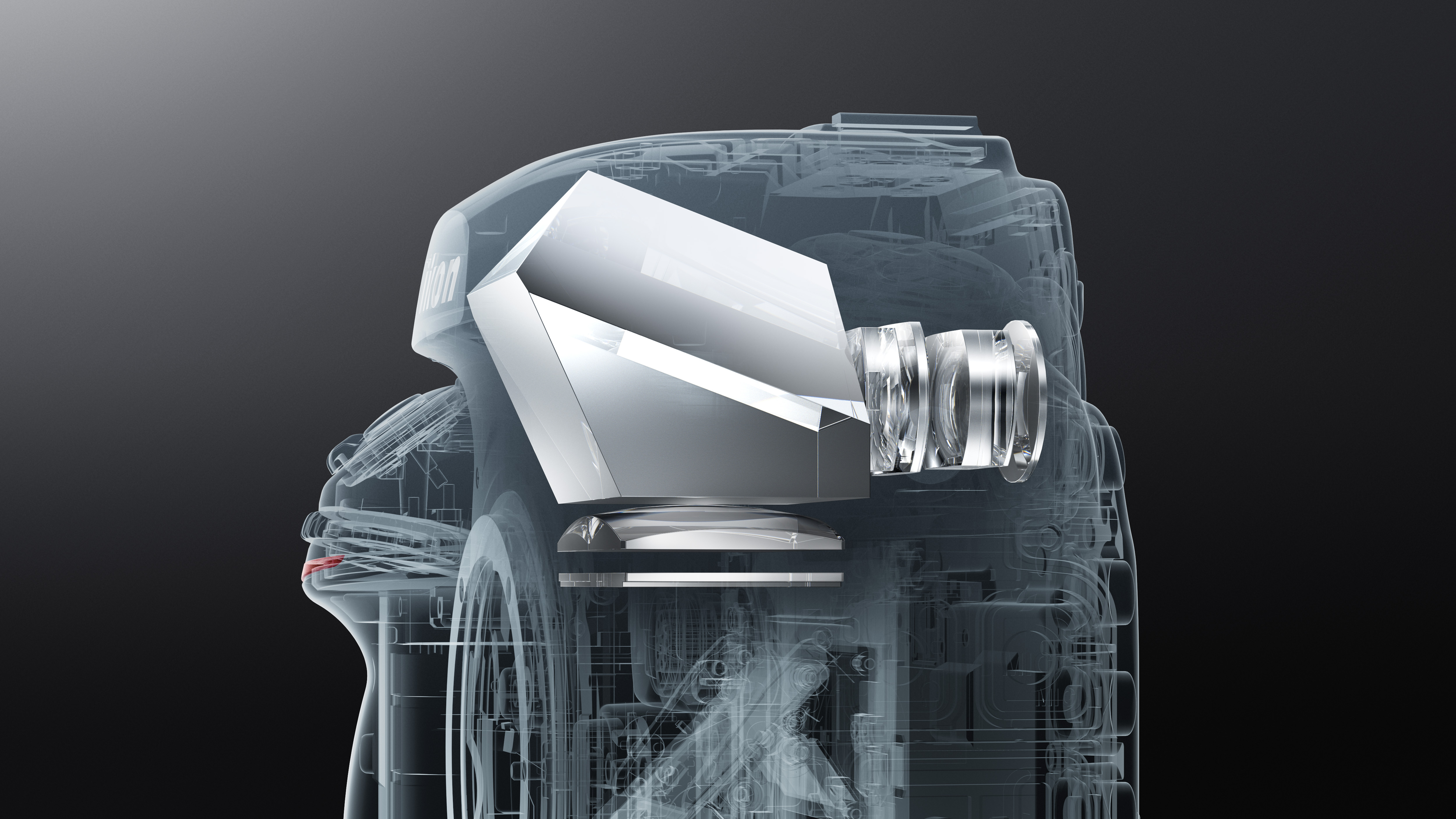

This is the type you get with DSLRs. You see the scene through the camera’s own lens, and this is achieved with the mirror inside the camera body, which reflects the image up into the viewfinder right up until the moment you press the shutter button, when the mirror flips up and out of the way. The single lens reflex is the only camera design which gives you this optical view through the lens, and it’s still the favourite camera type amongst many photographers today.

The specifications for an optical viewfinder will include its coverage of the camera frame (100% is obviously best, but some more affordable entry-level models feature 95% coverage) and its magnification (higher magnifications give you a larger viewfinder image).

Electronic viewfinders

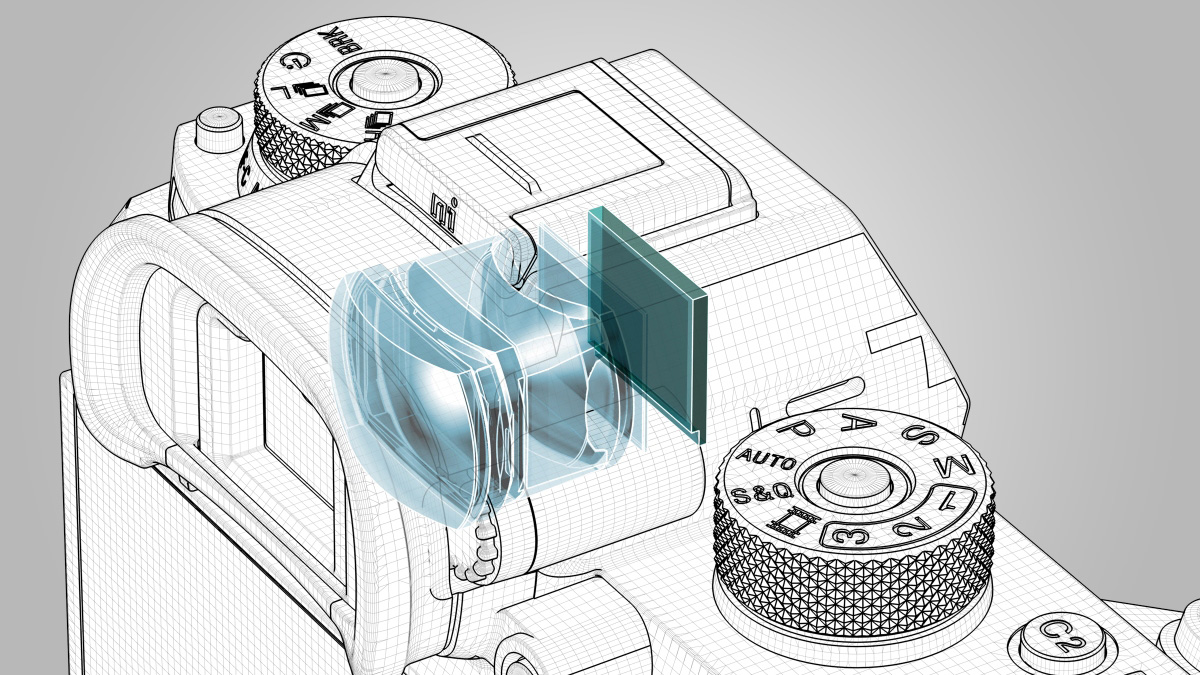

Also called ‘EVFs’ for short, these also show you the view through the camera lens, but this time you’re looking at a small digital display, which shows a live view straight from the camera’s sensor. Technically, there’s little difference between an EVF and the screen on the back of the camera, except that the EVF uses a smaller screen shielded from the light and magnified by the viewfinder eyepiece.

Mirrorless cameras use electronic viewfinders because there’s no mirror in the camera body to create an optical image – hence why they’re called ‘mirrorless’ cameras to distinguish them from DSLRs.

Electronic viewfinder specifications will include their resolution (in millions of dots), their magnification and, sometimes, their refresh rate (a faster refresh rate means less lag).

Optical viewfinders vs EVFs

There is an ongoing debate amongst photographers about DSLRs versus mirrorless cameras, and part of this revolves around the pros and cons of optical versus electronic viewfinders.

Optical viewfinders are typically sharper and clearer and, because you’re using your naked eye rather than a digital display, your vision adapts automatically to different lighting conditions. You see in the viewfinder what you see with your naked eye when you move the camera away.

Electronic viewfinders often have a faint ‘granular’ appearance because of the tiny dots that make up the display, and there can be some viewfinder ‘lag’ if you move the camera quickly. But a digital display can show you the scene as it will be rendered by the camera’s current settings – so you get to see the effect of exposure and white balance adjustments, or any special colour modes or effects offered by the camera.