As photographers, many of us become infatuated with new gear, such as a new flash, tripod, or lens. We scrimp and save our money, and go off to the camera store to purchase that new lens we’ve had our eye on, most times satisfied with whatever new piece of kit has found its way into our bag. Sometimes, though, it happens that for some reason that new gear we’ve spent our hard-earned money on doesn’t live up to our expectations.

Fast lenses enable the photographer to use shallow depth of field creatively. A 24mm f/1.4 lens, shot at f/1.4 was used for this image.

It may be that it was overhyped, or it doesn’t suit your workflow. There are occasions, however, when a piece of gear has a learning curve attached to it that needs to be solved before you can fully enjoy it. One such item that seems to have that learning curve attached, is a fast lens (one with large maximum aperture).

At some point, we all begin dreaming of fast (large aperture) lenses. For the purpose of this article, I’m going to define fast lenses as ones with maximum apertures wider than f/4.

Fast lenses are great for a lot of things, shooting in low light being one of the major advantages, because the wider aperture allows more light into the imaging sensor, which in turn allows you to use a faster shutter speed. This is why lenses like the 70-200mm f/2.8 are such a workhorse in a photojournalist’s camera bag. Another advantage to the wider aperture is the ability to create shallow depth of field in your image, which can make your subject really stand out from the background. The 85mm f/1.4 is one of my go-to lenses for almost any portrait situation for just that ability.

When photographing portraits, focusing on the closest eye is ideal when using shallow depth of field.

That all sounds great, right? But it’s that last point regarding shallow depth of field which seems to create the biggest problems for most photographers, who are new to using a fast lens. I often hear of photographers complaining about a lack of sharpness in their lenses, and more often than not, the issue crops up when the photographer is using a fast lens.

It may be a portrait photographer trying to use an 85mm f/1.8 wide open, or someone doing street photography with a 35mm f/1.4, and for some reason there’s a lack of sharpness to the image that will invariably be blamed on the lens. In my 20 years in photography, I’ve owned and worked with a lot of gear – 0ver a dozen different camera bodies, and several dozen lenses I’ve used at one point or another. I can honestly say that I have never once had one come straight out of the box brand new, and not be in perfect working order, so treat that option (that the lens is faulty) as a last resort for now.

Understanding Depth of Field

In addition to their low light capabilities, many photographers purchase fast lenses simply because of the ability to shoot with a shallow depth of field. When used creatively, a lens with a large aperture used wide open, allows you to be very selective in what you show the viewer, and what you hide in soft out of focus areas, known as bokeh.

However, it’s very important to understand that depth of field works differently dependent on the lens you are using. For instance, a lens such as the Nikon 85mm f/1.4 will have paper thin depth of field when used at f/1.4, at close distances to the subject. As the subject moves further away from the camera, that depth of field becomes a little greater. But at the minimum focusing distance, you could focus on an eyelash on your subject, and still have the eyeball be out of focus, despite the fact it’s only half an inch behind the eyelash. Assuming you don’t want to back up and change the framing on your subject, the best way to ensure sharp focus on the eye, is to choose a focus point on the eye and be careful it does not accidentally focus on an eyelash.

If you are willing to sacrifice a bit of that shallow depth of field, simply stop down a bit to give yourself some leeway on where you focus. While at f/1.4 or f/1.8 you may not be able to get both the eyelash and the eye in focus, but at f/2.2 or f/2.8, you’ll likely have enough depth of field to achieve sharp focus on both.

Using a 24mm f/1.4 lens wide open, setting the focus distance to the hyperfocal distance, allows you to get greater depth of field even when photographing wide open.

Even on wide angle lenses, such as a 24mm f/1.4 or 35mm f/1.4, which have inherently (seemingly) greater depth of field due to the nature of wide angle lenses, you’ll still notice some issues arising due to the use of a wide open aperture. If you can step back from the subject, you can increase the perceived depth of field since you’ll be focusing further away. You can calculate how far away you need to be by using a hyperfocal distance calculator.

The hyperfocal distance is the closest distance at which a lens can be focused, while still keeping objects at infinity acceptably sharp. In the shot of the upended bus at night, knowing the bus was about 30 feet away, I calculated the near limit of focus for the lens I was using at about 18 feet and the far limit was 91 feet, meaning anything past that distance would still be out of focus at f/1.4. By focusing at the hyperfocal distance of 44 feet, I knew the bus would fall into the area of sharp focus, while still keeping the stars in sharp focus. This is true because the hyperfocal distance is where everything from that distance to infinity falls within your depth of field, and everything from the hyperfocal distance to the point halfway between the camera and that distance, also falls within your depth of field.

Unfortunately, it’s not always possible to focus at the hyperfocal distance. For instance, photographing at a party in a dimly lit room, you may notice some areas out of focus due to the shallow depth of field. The fix here is to stop down a bit if you can. If you need more light, consider using a flash if appropriate, and stopping down the lens to give greater depth of field. Another option is to raise the ISO a bit to allow you to stop down the aperture more.

You may find yourself saying, “I didn’t purchase a fast lens to use it at a smaller aperture!” While that may be true, if you find yourself unable to capture sharp images due to the shallow depth of field, stopping down is the best solution. Please keep in mind, I’m not talking about a lens that just isn’t sharp. I’m talking about a lens that, due to its fast aperture, isn’t capable of capturing the depth of field needed to keep everything that you want sharp in focus.

Choosing Your Focus Point

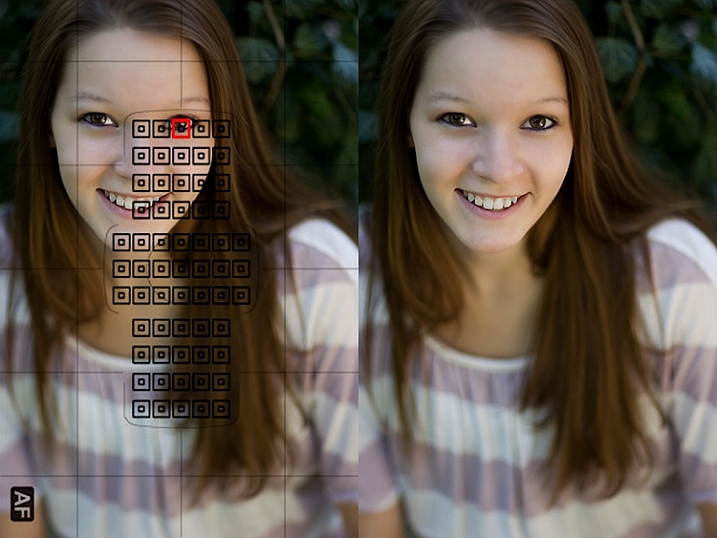

When it is critical to focus on a specific area in the image, choosing the correct focus point will ensure sharp focus where you want it, even when using a wide aperture with shallow depth of field.

One of the best things you can do when using a fast lens, is to ensure you’re focusing precisely where you think you are focusing. You want to be sure your camera is set to allow you to manually choose a focus point. By manually selecting a focus point, you can ensure the camera focuses on what you think it should. Most cameras default focus point selection method is automatic. In this mode, the camera will generally try to focus on the nearest object with detail that is covered by one of the focus points. Allowing the camera to choose can be a recipe for disaster, since quite often, the nearest object with detail is not what you want to focus on.

One of the best things you can do as a photographer is take control of where your camera is focusing by selecting the focus point that you want, and ensuring that the focus point you choose is on the subject you want to be sharp. Cameras today have multiple focus points, with some having as many as 61 AF points. While it’s true that generally speaking the center point will be the most accurate of those points, technological advances have made the points along the outer edge much more accurate than in the past. This means that you can choose those outer focus points with confidence when composing your image.

Using shallow depth of field on a portrait allows the photographer to focus on the eyes, and lets the rest of the body fall out of focus. An 85mm f/1.2 lens was used here.

Another related problem to the camera choosing the wrong AF point, is photographers employing a technique known as focus and recompose. This technique came about back when cameras only had a few AF points bunched around the center of the viewfinder. In many situations, it’s not a problem, as long as you are using an aperture that will provide adequate depth of field to maintain focus on the object or person you’ve focused on.

However, when using a fast lens, at a wide open aperture, focusing and then recomposing your shot becomes a real problem. This is because when using a fast lens at a wide aperture, the depth of field is so thin, that recomposing the shot will actually shift the plane of sharp focus away from the subject you initially focused on. So while you may have focused on the correct subject, using the center AF point, in adjusting your composition you knocked your subject right out of focus again. The solution for this issue is the same as above: manually select an AF point that you can place right on top of your subject, without recomposing your shot.

Embrace the Bokeh

Shallow depth of field can be used to create interesting effects and force your viewers to look where you want them. This image was made with a 70-200mm lens at f/2.8.

Lastly, in answer to those who bought fast glass to shoot it wide open, I say – embrace the bokeh! Bokeh is defined as the visual quality of the out of focus areas of an image, and each lens renders these areas a bit differently. Fast lenses typically have beautifully smooth bokeh.

Compose your shots so that the shallow depth of field is used creatively. To do this, you’ll need to understand what you can and can’t do when shooting wide open. Knowing that you will have a shallow depth of field, you’ll want to avoid stacking subjects at different distances. Create compositions that contrast sharp areas, with out of focus areas. Use that contrast to highlight certain objects within your frame, and by the same token, hide other objects by causing them to be drastically out of focus.

Using shallow depth of field allows you to highlight one object in sharp focus against a blurry background. This image was made with an 85mm f/1.2 lens.

Images created using shallow depth of field force your viewers to look where you want them to, because the eye is naturally drawn to areas of sharp focus. By using proper focusing techniques, you can ensure the image you see in your mind is the one you capture, and by understanding how the lens will handle depth of field, you can ensure that you’ll know to stop down when you need to for added depth of field, avoiding the mistake of having an important part of your image out of focus.

What’s your favorite fast lens to work with and why?

The post Fast Glass: Tips for Working With Wide Aperture Lenses by Rick Berk appeared first on Digital Photography School.